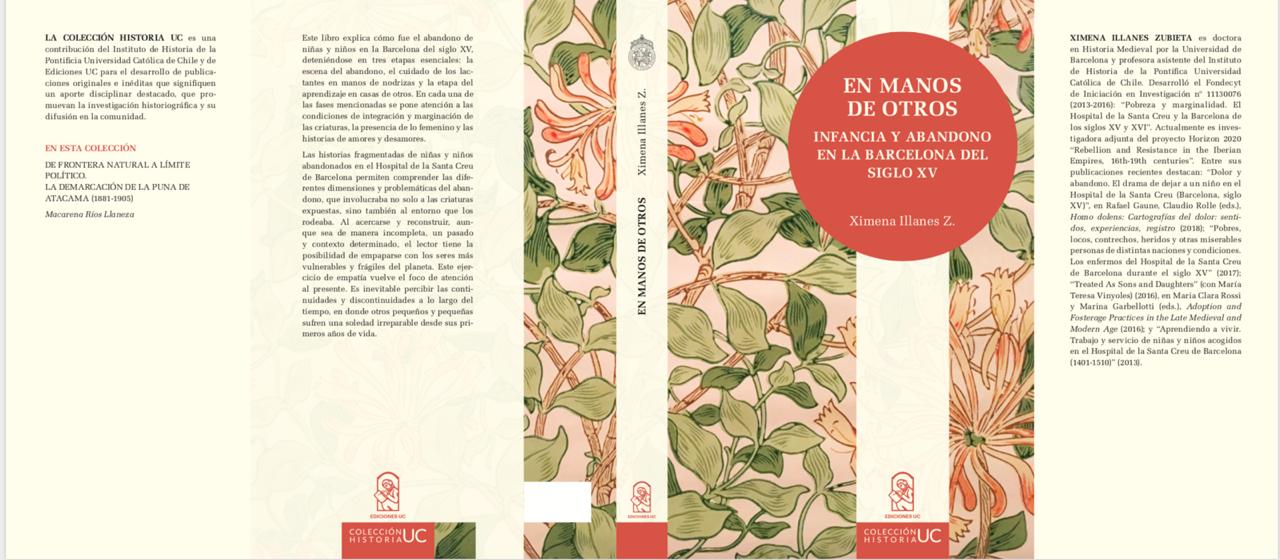

“In the Hands of Others. Childhood and Abandonment in Fifteenth-Century Barcelona” is the title of the book by this professor, a doctor in Medieval History, recognized for this important Catalan award.

How was the abandonment of girls and boys in 15th century Barcelona is the subject of the doctoral thesis of the Institute of History professor, Ximena Illanes, and which gave rise to the book published by Ediciones UC, which addresses three moments: the scene of abandonment, the care of infants in the hands of wet nurses and learning in other people’s homes. In each phase themes such as integration and marginalization, the presence of the feminine, and stories of love and heartbreak arise. The work was awarded by the city of Barcelona in the Agustí Duran i Sanpere d´Història category, as a contribution to the history of Catalonia, its people, and its memories.

What does this recognition mean?

I am deeply moved. On the one hand, because of the importance acquired by abandoned girls and boys, absent mothers, wet nurses, hospital staff, men and women of the city, in a period when they were made invisible, something not very different from what happens today. On the other, because by problematizing the poverty of an era, it shows the most vulnerable population, the one that has long been silenced by historiography itself, building a forgetfulness about key actors for the social development as they were -and they have been- lonely women and abandoned boys and girls. It is interesting to see how research linked to medieval studies can echo us today. For me, this is the importance of this book: the present of Catalonia, which finds in the result of this doctoral research, a grain of sand to understand its present. Finally, and for all the aforementioned, this award fills me with joy. Catalonia was not only my object of study, which thanks to its archives allowed me to apprehend it, but also Barcelona was the place that welcomed me, where I was nourished by new ideas, where I forged great friendships like my thesis director Dra. Teresa Vinyoles. This recognition is also a way of saying thank you for giving me the opportunity to delve deeply into your identity.

What does it mean for UC to have been awarded this award?

I believe that the fact an academic from UC receives this recognition reflects how our institution has been internationalizing in an increasingly globalized society. This is one example of many others, which concretely make visible the effort of the UC community, to dialogue, discuss and investigate in the most different areas and regions of the world. The fact that the borders are being diluted, allows creating teams of work, networks and vital connections for the advancement of knowledge, broadly speaking.

This book was born from the development of your thesis, do you intend to continue delving into this topic?

Yes, this book has its origin in the doctoral thesis that I defended in January 2011. Addressing childhood as a category of analysis significantly marked my evolution as a historian, which was supported by our current contingency: the crisis that today is known to everyone when it comes to the children’s human rights. In this sense, the last two years, I have delved further into the subject from a more current temporality, forming multidisciplinary teams with psychologists, psychiatrists, among others. That allowed us to understand the issue in a broader way and that, in turn, build inputs to generate policies that allow us to advance the rights of girls and boys. History is not a dead past, but rather it is a present that gives us light to look at ourselves and project our future. For this reason, I hope to continue contributing from this field with regard to childhood without abandoning the Middle Ages, as a laboratory for the present.

Why did you choose to investigate the abandonment of girls and boys in 15th century Barcelona?

It is impossible to answer this question without going back to those lectures and seminars that, from different perspectives, aroused my curiosity and stirred me up when I was studying for my degree at UC. José Marín, Claudio Rolle and Nicolás Cruz, in addition to other professors who are my colleagues today, encouraged me to follow my instincts and do a doctorate in Medieval History at the University of Barcelona. There are many specialists and texts that have influenced this research. I highlight The Mercy of Others by John Boswell which deals with abandoned girls and boys from Roman times to the end of the Middle Ages. This author proposed that the forms of abandonment were relevant, since leaving newborns exposed to the elements, at the doors of a house or church, had a different impact on them in relation to those who came to specialized hospitals for it; the latter carried with them the stigma of marginalization because the entire population knew the institutionalized children. What Boswell never knew, on the contrary, the fascination that the text provoked in me installed on my horizon a greater challenge that ended up nourishing the doctoral project. Added to this, is the information that filled the shelves of the Archive of the Hospital de la Santa Creu y San Pau in Barcelona. That encounter with the manuscripts and volumes about foundlings and wet nurses activated my senses: both the wealth of information and its materiality, that is, the typography where the words intertwine, the binding that treasured the leaves of a social and social fragility, and the same archive, a space that welcomed these helpless women and infants. It was love at first sight.

Do you see any similarities with the situation of childhood in Chile today?

Yes, the vulnerability to which girls and boys have been exposed is historical. One can see how, from the transformations of societies, a category such as childhood begins to be built, which improves the condition of all the social actors that are a constitutive part of it, a network that includes mothers, midwives, church, state, etc. It is impossible not to link these cases to our current situation. In April 2016, while teaching the postgraduate course on poverty, charity and assistance in the Old Regime, the case of Lissette’s death exploded at the Galvarino Center dependent on SENAME. This case spontaneously influenced the dynamics of the course: the present also filtered into our conversations. Together with the doctoral student Miguel Morales, we propose the need to reveal the absent children’s voices of the past as a way to measure and understand the latent drama of childhood of the most vulnerable in our country. This marked a beginning to study the early links that psychologists and psychiatrists have worked so hard to do, but that many times forget the historical context in which they have been generated and mutated: How much continuity and rupture? How much progress have we as a society in these matters?

I was more aware of how “In the hands of others. Childhood and abandonment in 15th century Barcelona ”constantly dialogues with our present, shedding light on understanding the impact of abandonment: the abandoned are the others, the stigmatized of a society. Deep down, I believe that there are obvious permanences with the most vulnerable childhood in this country, since the institutionalized children of SENAME continue to be the most marginalized and stigmatized of the population.

Through abandonment, are there other topics that you addressed in your book or that you would like to deepen?

Yes, child abandonment is a practice that is part of the social system where other instances and agents converge that provide feedback on the situation. The abandonment of girls and boys in the Hospital de la Santa Creu, for example, was related to various problems, such as maternity, sexual practices, the hospital space, the exercise of charity, material culture, the various solidarity networks, emotions and what poverty meant at the time. However, of all these factors, mothers and wet nurses became a relevant topic in the research, so I can affirm that the book is also a contribution to the history of women. It is not less than the women who abandoned their newborns were in a vulnerable and precarious situation, they were prostitutes or mentally ill, branded as crazy in the records; women-mothers who expressed their pain by leaving their children in the hands of others. There were also the nursemaids who cared for the little ones for the love of God, although some of them charged for breastfeeding establishing a kind of business, others were instead slaves and fulfilled the mandate of their owners when the mother did not have access to milk, a practice that was maintained – and in some cases continues – until well into the 20th century. This meant rethinking motherhood or existing motherhoods, reflecting the tensions between the cultural and biological, laying the foundations to measure the crossroads between religion and medical science, the imaginary of the nursing Virgin and the ideals of medical treatises.